The New Technology of Teams

How Organizational Network Analysis Can Increase Team Collaboration

This is the Workforce Futurist Newsletter about the rapidly changing world of work. Please subscribe if you don’t already for regular posts and longer essays (like this) direct to your inbox every week.

This essay was a team effort by Andrew Spence and Francisco Marin. If you prefer, you can also read this in spanish or portuguese.

All great work happens in teams.

Think of the achievements from your favorite sports team, vaccine development collaboration, or local healthcare team. There are great accomplishments despite the fact that many management and HR processes are designed around the individual. This is a challenge for leaders who are responsible for ensuring that organizations have the right infrastructure, tools, and culture.

As industries respond to the Digital-Covid Age, there will be a wave of mergers, acquisitions, and restructuring. Various studies have reported high failure rates from integration and change programs, so it is important to think through how to ensure that goals are achieved.

We do not know the future state of our organizations, but we do know that work will be completed by diverse specialists with a range of employment relationships from employees to freelancers. Sometimes this work will be completed in virtual teams outside of traditional hierarchical structures.

How is Teamwork Changing?

The days of trying to design organizations by switching boxes on PowerPoint diagrams and keeping track of budgets on an Excel spreadsheet are long since gone.

As work is gradually moving away from hierarchies of talent to teams of collaborative networks, we need a new set of tools to understand team dynamics. Leaders need new tactics to motivate, coordinate and align networks of teams, share information, and work collaboratively. Command and control top-down approaches will not work in many situations.

The way teams are formed and operate is not always predictable. They may not go through linear phases of storming, norming, and performing (Tuckman) – but a body of scientific evidence has emerged on which teamwork factors lead to a positive impact on organizational performance.

Successful teams use tactical training interventions, adopt coaching at team level, and have clarity around purpose, goals and behaviour. High-performing teams regularly take time to reflect together and hold effective one-to-one meetings.

There is an increasingly decentralized workforce as many people work outside of organizational structures, from hourly experts, platform workers to live-streamers, and creators. These distributed workers are not all working in isolation but forming new alliances and collaborations.

This decentralization trend is paired with an increase in remote work, which results in a pressing need for companies to effectively understand and manage internal collaboration dynamics.

A new set of tools and platforms are being developed that will form a new infrastructure of work. These include industry standards in verifiable digital credentials, peer-to-peer platforms, and, decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs).

From Organization Charts to Insights from Organizational Network Analysis

Over the last few years, Workforce technology has included more employee sentiment analysis. Although this is more sophisticated than the annual employee engagement survey, it still relies on responses from an increasingly jaded workforce.

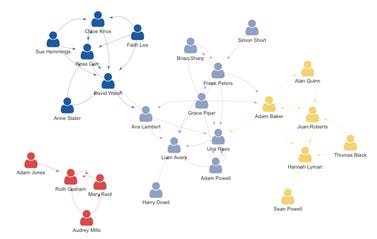

Another useful set of data to look at when solving business challenges is from employee’s actual behavior, using Organizational Network Analysis (ONA). This measures patterns of collaboration by analyzing the interactions between people in networks, moving away from the static hierarchical views of organizations. It identifies more useful patterns in terms of roles in networks such as central nodes, knowledge brokers, and those on the periphery of the network.

‘Active ONA’ surveys look at how groups of employees feel about their colleagues and relationships in the organization. This method can identify informal influencers who might not always be at the top of the traditional organization charts. Informal leadership and influence are based on subjective perceptions, it is only by directly asking employees we can properly identify the informal influencers within the organization. Active ONA is the most useful tool here and used to support effective onboarding, change management and leadership development. Active ONA provides a snapshot of the collaborative networks of the organization at a particular point in time, and it is best complemented by passive ONA.

‘Passive ONA’ provides a complementary view of how teams are collaborating by analyzing communication patterns, for example from email meta-data of collaborative tools like Office 365. This can provide insights on a regular basis by monitoring teams’ digital footprint and has proven to be effective when assessing productivity and burnout risk.

An ideal approach is a combination of active ONA at an employee level and passive ONA at aggregate level, providing actionable insights, but also protecting employee’s privacy.

It is essential that any project utilizing people analytics, including organizational network analysis operates with clear ethical guidelines. Any initiative that risks employee trust will erode the goals of the project.

From a data privacy perspective, active ONA is relatively straightforward because employees provide their consent when completing the survey.

In the case of passive ONA, each employee would need to explicitly provide consent in order for their metadata to be analyzed at individual level, therefore it is more efficient to perform the analysis only at aggregate level. This way, companies respect employees’ privacy and accelerate the internal approval cycle when presenting a business case for a passive ONA deployment.

How are Organizations using ONA?

Active ONA has also been useful in onboarding, by identifying informal leaders, who can be ‘buddies’ to new hires in order to accelerate their time-to-productivity and enhance their overall employee experience. Where the majority of workers are working at home, this can be even more crucial to get new team members up to speed in their work.

Another common Active ONA example is in change management, where informal leaders are positioned as early adopters to accelerate strategic change adoption. For example, a 45,000 employee corporation, using ONA technology from Cognitive Talent Solutions, identified informal leaders to act as super-users for a change program. This accelerated the program adoption and saved $161k in process improvements.

Passive ONA can help companies assess employee burnout risk by monitoring indicators in the employee's digital footprint such as the percentage of communications outside of working hours, the percentage of unread messages, or the average response time.

This technique enables companies to identify potential employee burnout scenarios and implement mitigations when needed. For example, a Fortune 500 biotech company, created summaries at the division level highlighting predictive and prescriptive analytics on burnout risk, and productivity. They combined Passive ONA’s aggregate-level insights with Active ONA’s individual-level insights. The company was able to analyze changes in the organization’s internal collaboration dynamics in real-time. This allowed them to accelerate strategic change adoption and implement more informed mitigation plans.

Looking at collaboration patterns can also help identify where there are lower levels of trust in the context of mergers, and acquisitions. Understanding which employees are the informal leaders can be useful to prevent or mitigate cultural clashes during the post-merger integration. An example of a business benefit was to help accelerate the realization of IT synergies by accelerating the replacement of legacy systems by new centralized. Once the integration is completed, ONA can also help companies understand the level of integration between legacy organizations and its impact on their performance.

ONA has proved to be effective in diversity and inclusion initiatives. Monitoring collaboration patterns in the organization by gender, age and ethnicity, can highlight potential conflict areas where intervention might be needed.

What Leaders Can Do To Support Teams

To better support teams in organizations, leaders can take the following actions.

Think broadly about designing work, and who is best placed to do that work – from employees to vendors, automation, or freelancers. Monitor the optimal combination of employees, contractors, or machines to carry out a package of work.

Seek out a broad set of evidence, within your industry and from relevant academic research, to examine what will improve team effectiveness in your organization.

Evaluate new technology tools available, including ONA to support business challenges around onboarding, change management, leadership development, productivity, burnout, mergers and acquisitions and diversity and inclusion.

HR’s role in the future will increasingly focus on nurturing talent networks, evaluating workforce tools, and monitoring organizational effectiveness.

The next wave of successful organizations will adapt to changes in the workforce and provide tools to support the foundation blocks of our organizations – our teams.

If you found this article interesting, then please share with your network.